The argument of this essay is that the best way to theorise modernist art, now, is to consider its relation to the value-form, or, more specifically, to the temporal structure of that form’s anticipated overcoming in different phases of the development of the class relation under capitalism. What follows are notes towards a more thorough treatment of the problem. My frame of reference is the discipline of art history. I am responding, in part, to previous work on the break between a pre-World War II ‘historical’ avant-garde and the so-called neo-avant-garde of the postwar period, in texts by Peter Bürger, Benjamin Buchloh, and Hal Foster, among others.[1] This discourse has arrived at an impasse; I aim to get out of it. The broader methodological stake of my inquiry is to suggest approaches for a new materialist history of art – one adequate to current forms of anti-capitalist struggle. To this end I draw on communisation theory and value-form theory.[2] At the same time, I want to maintain a tension between whatever of my argument can be recruited to academic art history and what (perhaps) cannot. If this essay succeeds it will bite the hand that feeds it.

First, though, we should arrive at a preliminary sense of what is meant by the term ‘avant-garde.’ Consider a paradigmatic case.

Constructivists in Lenin’s car, Moscow, 1918

There is a photograph that was taken near the Kremlin in the summer of 1918. Four men sit in a Model T Ford. The man at the wheel is Gustav Klucis. At far left is Karl Ioganson. Both were members of a contingent of Latvian machine gunners assigned to guard duty in Moscow shortly after the Revolution. Both were also modernist artists. The automobile in which they pose belonged to Lenin himself. Over the next few years, Klucis and Ioganson would become protagonists in the movement known as Constructivism, before moving on to political photomontage and direct engagement with industrial production, respectively. In the mid-1920s, Ioganson struggled through a post at Moscow’s Krasnyi Prokatchik (Red Roller) metalworking factory, serving as an ambiguously defined ‘organiser of production.’ He eventually gave up and returned to Latvia, where he managed socialist vacation colonies until his death from natural causes in 1929.[3] Klucis, a victim of deeper ironies of history, was to die in the Great Purge of 1938, after having spent his last decade as a propagandist for Stalin’s regime.

I begin with this calamitous trajectory because it says something about the avant-garde in general. What was it, anyway? The parable of the Constructivists in Lenin’s car suggests that it was a certain proximity to revolution: not to the idea of revolution, but revolution as a concrete reality. And it suggests that the destiny of the avant-garde was tied to revolution’s failure.

These will be uncontroversial claims with respect to the early Soviet experience; less so when we turn to Futurism, Dada, Surrealism, and De Stijl, and even less for Cubism and abstraction. Yet it is evident that these various modernisms constitute a field in which broadly common stances towards futurity, negation, and the materiality of art’s procedures could be modulated across the vastly different conditions of, for instance, Civil War Russia and Return to Order France. It is this field of shared horizons that is at issue here. (It will be evident that I do not accept a firm distinction between ‘avant-garde’ practices, such as Dada, supposedly characterised by negation, and ‘modernist’ practices characterised by formalist concerns; this strikes me as an essentially post-1945 construct tailored to the needs of autonomy’s partisans.) I will turn, then, to another example, not at the polar opposite from the Constructivists, but sufficiently distant to test my proposition’s validity.

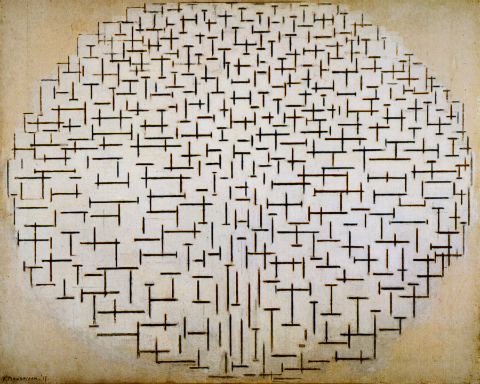

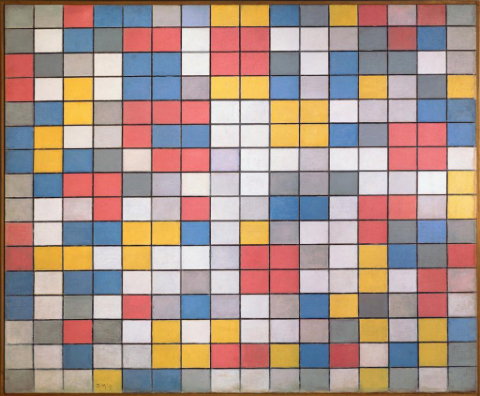

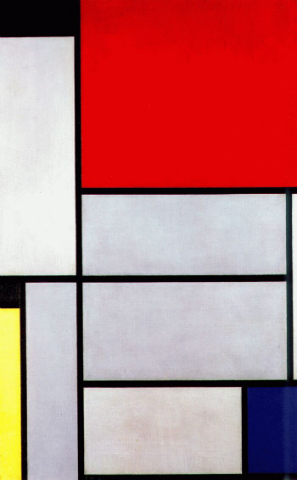

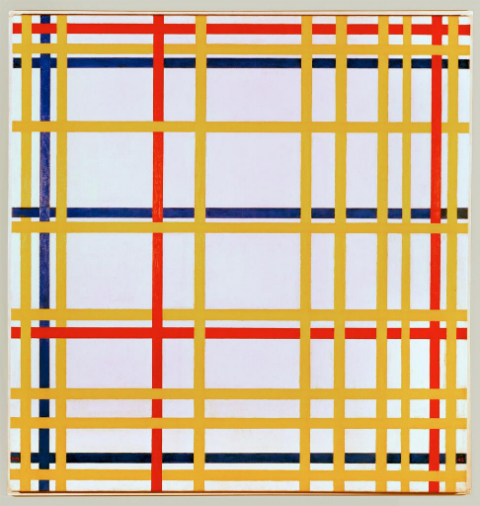

The art historian Yve-Alain Bois has shown how Piet Mondrian’s practice shifted, around 1921, from experimentation with tautological structures to the reinvented classical composition of his mature Neoplastic paintings, which solve the problem of figure-ground hierarchy without recourse to the naturalised indexicality of the pure grid.[4] The paintings of the earlier 1910s still betrayed their origins in realistic motifs. The artist’s encounter with Cubism then suggested several ways to pry loose the unit of the mark from its dependency on mimesis. The Cubist grid could be a kind of tessellation, or, alternately, a more open zone of coalescence; in either instance, however, it still carried a residue of traditional pictorial space that Mondrian was to find increasingly intolerable.[5] The option he essayed in the two years after World War I – a completely regular, allover grid – proved unsatisfactory: it turned out to be another form of naturalism, thanks to its reliance on blind repetition, and moreover it resolved the tension between depth and flatness too wholly in favor of a single undifferentiated plane.[6] The Neoplastic paintings, by contrast, would keep the image in flux by reintroducing problems of balance and scale (the relation, especially, of each element to the edge of the picture). Mondrian also ingeniously annulled the polarisation between line and colour by expanding his characteristic black strips just enough to register simultaneously as plane and boundary. That he was able to do all this without surrendering to either figuration or illusionism is an extraordinary feat: the paintings are all figure and all ground at once. Ultimately, though, Mondrian perceived the ground itself as a problem – nothing more, in the final instance, than another pictorial convention to be negated. Hence the artist’s last works, from late 30s to his death in 1944, destroy their own flatness and instead weave bands of colour into a perpetually open matrix – neither the registration of a literal plane nor the illusion of a fictive space. These are pictures that belong, as far as possible, to No-Place whatsoever, which is the literal meaning of Utopia.

Piet Mondrian, Composition 10 (Pier and Ocean), 1915

Bois shows how Mondrian traveled this via negativa to a series of formal inventions. Each step anticipates the next, or at any rate anticipates that there will be a next step. At the end of it all there is perhaps still a vision of totality: the completely reconciled artwork as a figure of reconciled society, maybe even its prerequisite. Yet to sustain this aspiration to totality Mondrian’s practice had to methodically destroy its own closure. Every solution to a problem recomposed itself as another problem, another limit to overcome, though also, in each instance, another provisional totality or self-sufficient system. It is not adequate to describe Mondrian’s achievement as wholly positive or wholly negative, wholly classical or avant-garde. Rather, it was, like modernism at large, a practice that reproduced itself, or posited its own presuppositions, only at the cost of repeatedly throwing itself into the negative and hence confronting the limits beyond which it would cease to be legible. The picture was to be a sum of destructions, as Picasso once said of his own art.

Piet Mondrian, Composition with Grid 9: Checkerboard with Light Colours, 1919

This is perhaps as good as modernism gets. It is interesting, though, that for Mondrian as much as, say, Francis Picabia, or Karl Ioganson for that matter, the modernist mode carried in its heart an extremism that could become hypertrophic in its best and worst phases alike. The drive towards self-overcoming that Mondrian limited to pictorial abstraction was not fundamentally different from the one that led Ioganson from the studio to the factory to the eventual desertion of art, or that led Klucis from Malevich to Stalin. In any given instance of modernism at its highest intensity it was the possibility of the mark itself that was at stake: whether line or colour or shape could be adequate to history and still be recognisable as art, and whether the artist’s subjectivity could be adequate to the making of such marks. Modernism mediated that limit and made it into form. Art courted reification when it failed to confront the limit of its reproduction as an institution – whenever, in other words, it started to look too much like art – yet it risked still more disastrous reification when it exceeded that limit, as the late work of Klucis demonstrates. Either possibility was built into modernism’s basic procedures.

Piet Mondrian, Tableau 1, 1921

What we call the ‘neo-avant-garde’ is the last cycle of artistic production that can still plausibly be said to have made claims in the terms sketched above. It is evidently not a concept that admits of strict periodisation. For simplicity’s sake let us postulate that the neo-avant-garde’s terminal phase, in Western Europe at least, begins in 1957, when Guy Debord and others founded the Situationist International. Most likely it ends in the 1970s – perhaps, for instance, in 1979, the year when the Italian state arrested leading figures associated with the nebulous phenomenon called Autonomia. Between these signposts lies the death of what some theorists (I am thinking particularly of the French group Théorie Communiste) have defined as ‘programmatism’: briefly, the cycle of class struggle – conspicuously coterminous with artistic modernism – that finds its programme in the affirmation of the proletariat as an autonomous pole within the capitalist class relation. Programmatism refers to struggles that affirm the identity of the proletarian subject and hence that frame politics in terms of the growth of class power, as opposed to the immediate abolition of the proletariat as a class of capital. It begins with the workers’ movement in the mid-19th century and ends, if we follow the concept’s originators, in exactly the moment in question, the 1960s and 70s, when new forms of revolt and capitalist restructuring eliminated the basis for a programmatic class politics. Workers themselves then tended to reject mediation by traditional parties and trade unions, while capital decomposed the class through a new global division of labour and intensified real subsumption of the labour process (by which I here designate the imposition of specifically capitalist rationalities through technique and organisation). What does it mean to say that modernism ‘belongs’ in some deep but still-to-be-determined sense to the epoch of programmatism?

It means that we should grasp modernist art’s self-preservative and self-destructive moments in terms of its constitutive relation to the value-form. This is a large claim. All the same, the premises of my argument are simple observations.

Under capitalism, art is and is not like any other commodity.[7] It is and is not like any other congelation of abstract labour time. It occupies something like a permanent gap in the structure of value’s reproduction, and hence is in contradiction with the value-form even as it is nothing other than this relation to it. During the epoch of programmatism, it was the specific form of this contradiction that accounted for art’s positivity, as a practice that was able to sustain itself, indeed to thrive on its predicament, at least for a time. Modernist art was also negative because it stood for everything beyond the law of value. In certain of those extreme moments that defined its very being, it was nothing less than the concrete figure of utopia. As such, however, it perhaps remained a specific and conflicted instance of the value-form’s own properly utopian content, which is to say its prefiguration of a socialist mode of production that would be even more thoroughly mediated by labour than is capitalism, though under the conscious direction of its human bearers. Hence if class consciousness in its Lukácsian formulation is the self-consciousness of labour, recognising its own alienated essence in the commodity-form, modernist art could be described as something like the moment of value’s self-reflexivity, when it pauses in its circulation and dithers. Modernist art is value thinking its own sublation.

Art could play this role only by continually defying its relapse into identity with the value-form. This required an immense labour of the negative. At the same time, art had to assure its reproduction as an image of value’s blocked totalisation, which is to say, as an image of the dictatorship of the proletariat, or the transitional phase, or any other placeholder for a future social order grounded on labour in the form of value and hence on reproduction of the class relation. Again and again, though, it was discovered that the preservation of art as the figure of utopia necessitated the destruction of art as a signifying practice, because signification itself was perceived as already captured. Artworks had to be opaque to the extent that utopia had to remain unrepresentable, lest it succumb to the fallen world.

The possibility of an entirely new kind of signification was one of modernism’s indispensable regulative ideas. But negation always came first. This is because modernist art projected its new languages into a future in which a social practice adequate to the new signification was expected to come into being – Mondrian is again representative. As a mark made within a given situation, however, any modernist artifact only made space for itself by working against existing codes, as their rupture. In practice this meant that modernism continually ran up against the materiality of its means as the truth of its mythic or utopian ambition, and that this mereness in turn had to be ideologically mediated. (Clement Greenberg’s later work does this.) Moreover, modernist artists also repeatedly found that their attack on signification threw them into perverse solidarity with the value-form’s own powers of dissolution. Words in liberty and arbitrary signs began to look like money, value’s most general equivalent. Here, it is the art of Picasso in the years around 1912 that remains exemplary. Disenchanting the sign turned out to leave it open to subsumption by the value-form, a process that Picasso himself soon felt it was imperative to resist via a return to outmoded forms of mimesis.[8] A bit later, some works by Duchamp and Picabia seem to have aimed instead to exacerbate the value-form’s deterritorialising effects and thus perhaps to undo its dominance by a kind of autoimmune response.[9] The ambiguity of this strategy is obvious and would become only more strained among those artists who took up its example after World War II. In all of these cases, it was modernism’s gambit to submit art to its opposites, value and non-signifying matter, as perhaps the last way it could still be made.

Piet Mondrian, New York City I, 1942

The next conceptual if not strictly chronological step was the destruction of art’s autonomy as an institution. Art had to be annihilated when its existence as a bourgeois cultural form seemed to exclude the realisation of its own promise of happiness. This emerged as an almost naturalised course of action in revolutionary or apparently revolutionary moments, for instance in Soviet Productivism and Berlin Dada. It was also anticipated in Italian Futurism, which likewise sought to dissolve autonomous art into politicised life. It is worth noting that very often what the avant-garde called ‘life’ can be more precisely described as the sphere of reproduction. This latter category’s eventual abstraction as ‘life praxis’ in later theorisations of the avant-garde promiscuously suggests a continuum between production and reproduction.[10] Yet it is reproduction that is tacitly asserted as the content of the everyday, because whatever emancipatory potential one could attribute to the collapse of art into ‘life’ cannot be drawn from alienated production alone, and hence must posit at the very least its infection by social reproduction: that is, subordination of production to actual needs rather than accumulation. For all of its frequent productivist (and masculinist) pretensions, then, it is more useful to describe the avant-garde as, among other things, a means of precipitating an altered relation between the two spheres – ultimately, their anticipated identity. We can thus say that the aim of the so-called historical avant-garde, albeit one that was perhaps not completely articulable until its recovery after World War II (that is, after an immense crisis of the capitalist everyday), was to reconcile production and reproduction under the sign of sublated value.

Yet all of this perhaps began much earlier, with Courbet’s realism, or Manet’s desacralised museum painting, both of which were not only attacks on the transparency of traditional representation but also profound attempts to figure newly emerging structures of reproduction. (Of course the results were intensely mythicised.) In turn, the death agony of modernism stretched at least through the 1960s. For about a century, then, it appeared to many artists that the realisation of art required its negation: first of its received forms, then of its fetishised autonomy, and finally of its very existence.

I say this knowing that the imperatives I am describing were only intermittently conscious to practitioners and critics of modernism, and rarely made up a programme. Neither did these stages of negation follow one from another in crude temporal sequence. Rather, the structure outlined here is a recurrent narrative form proper to the contradiction of the aesthetic as an aspect of the moving contradiction of capital during a certain phase of its development. The concept of programmatism clarifies the periodisation of modernism because it more precisely determines the relation between class struggle and the reproduction of value.

The value-form is a broken image of utopia. The forms of negation sketched above would make no sense unless art was felt to be, somehow, the repository of a quality lacking in capitalist modernity, a quality that could only be made available to society, however, by one style or another of art’s destruction. It is not the case that in every single instance this quality was in fact the liberation of labour – in other words socialism, or the reconciliation of humans with their own production and with nature. However, the fact that labour in the form of value is the most basic mediation specific to capitalist society means that there was in this era a structural propensity for liberation in general to be posed as the liberation of labour, so long as labour itself could still appear as the proletarian subject’s own truth, rather than as wholly subsumed to the reproduction of capital. If the affirmation of the proletariat affirms value as the worker’s own objectified essence, which it expects to be reappropriated under socialism rather than merely destroyed and stripped for its use, modernist art as the value-form’s utopian moment necessarily bears a relation to the dynamics of class struggle: not as something external (context or subject matter) but as the very ground of the artistic mark’s possible mediation with a social totality.

Class struggle in the shape of programmatism is internal to modernist practice, and inescapably so. Of course this does not explain everything about modernism. There are entire bodies of work and indeed moments in the works I have already discussed that speak to different questions. One could, if so inclined, attempt to draw these elements out of the identity-in-difference of art and the value-form, which is a mode of the more basic contradiction between use value and exchange value.[11] However nothing here will be worth saying unless it is taken up in much more finely textured readings of particular works of art. It is unfortunate that the degree of abstraction required to succinctly present my argument excludes precisely what was long the greatest strength of the social history of art: its ability to describe how artworks behave in specific conjunctures, how they relate to their audiences, how they mediate specific positions in class society, specific structures of representation. Nothing in my emphasis on the value-form is meant to indicate that scholars can now neglect such matters. Rather, we should ground those investigations anew in a more global understanding of how capitalism works.

At the least, the above schema allows us to reconstruct a continuity against which to register changes. Most obviously, we can observe that the modernist mode became increasingly worried as the 20th century rolled on and in particular after the disasters of 1933 to 1945. If the formal device of the grid had a social reality it turned out that this was not, or not only, the Corbusian city but the death camp. Modernism’s dominant expression then became a simpler ideology of autonomy, before collapsing altogether. Around the end of the postwar economic expansion, though, it was possible to say one last time that the beginning of life required the death of art. It was possible to identify a chiasmus, an exchange between the ‘The Revolution of Modern Art and the Modern Art of Revolution,’ as the English section of the Situationist International put it in a text of 1967.[12] It is this moment, it seems, that constitutes the threshold beyond which we still cannot pass when imagining the politics of art. It represents for us something like the final form of transitivity between political and artistic gestures. For the more localised practices of post-’60s art the late neo-avant-garde’s aspiration to totality is gone but not forgotten: it is their inaccessible apocalypse. The conversion from revolution in the aesthetic to political revolution evidently remains for us the one possible way of imagining art’s end and hence its realisation.

This moment is lost to us now and to revive its language is nothing but political nostalgia. It will be revived, has been revived; critics must deal with its revivals and the hopes they express, because in the present we often have little else with which to operate. Such phenomena are not mere holdovers but are rather immanent to the aesthetic field under the present changed form of the class relation. It is perhaps in the nature of modernism, like philosophy, to endure after the moment of its realization was missed. But this fact signals an impasse rather than recall to (dubious) past glories. The ossification of modernism’s last self-imaginings can and should be overcome, though not by modernist means.

I will propose a different chiasmus, then. Let us say that in the era of programmatism it was art’s self-destruction that was posited as the condition of the proletariat’s self-affirmation. In the era of programmatism’s fading, however, it is the horizon of the proletariat’s self-abolition that is the ground of the artistic mark’s mediation with the social totality and hence of art’s contingent phasing in and out with the real movement of that totality’s negation. And this is so because, after the fading of programmatism, or to put it differently, after a certain progress of real subsumption, the value-form itself – art’s secret sharer – ceases to be the alienated form of the proletariat’s positive and autonomous being and is instead produced in the course of struggle as a dead exteriority in which the proletariat finds only the image of its class belonging as something to be overcome. Value remains the category by which life and death are portioned out across the globe, and certainly not for productive workers alone; the growing significance of credit as opposed to the wage as a means of survival changes nothing about that. Yet decomposition of the working class means that hands have largely slipped from the levers. Capitalist development no longer homogenises the class worldwide but stratifies and disperses it. Capital throws off labour and creates vast surplus populations with no clear basis for unity at the point of production. Decoupling the reproduction of capital from reproduction of the proletariat becomes at once the result of the capitalist valorisation process, as the moving contradiction between necessary and surplus labour, as well as the break to be produced by the activity of proletarians: class war now is war over the results of a crisis in the class relation, not control over the workplace or the state. The value-form has ceased to project itself into modernist futurity as the anticipated basic mediation of a socialist transitional period, but instead faces the alternative of its reproduction, in capitalism, or its abolition.[13]

None of this is external to art but instead constitutes something like its ontology, since although the value-form no longer has a role to play in the affirmative apparatus of programmatism it does emphatically still determine the place of art in capitalist society. There is no ‘aesthetics’ proper to the kind of revolutionary action that could occur in the present moment, but only certain conditions of possibility that we can reconstruct in theory. The release of art from the programmatist dispensation with regard to value means that there is now a certain leeway or even an aleatory moment in the relation between art and concrete instances of struggle. This is the extremely qualified sense in which one can accept the sub-Hegelian notion that we are living during or after the end of art: it is not true that anything goes, but rather whatever goes has to be determined one case at a time. Art may never have had much to do with the absolute, but in the past two centuries it has had a privileged relation to value, which is the basic mediation of a capitalist social totality. When labour, that is to say the substance of value, ceases to be affirmed in class struggle, art takes on a new indeterminacy with respect to that totality. Art becomes open to the inscription of new subjects and to the appropriation of its marks by new collectivities, not necessarily, but as things ebb and flow.

The undoing of the modernist form of the relation between art, value, and futurity by the extension of real subsumption means that art cannot now be presumed to hold in reserve any qualities of essential use to a coming social order, because that sort of future – a future in which a coming mode of production could be planned and realised by a programme – no longer exists. To take an example: the dialectic of deskilling and reskilling, to the extent it ever held at all, is now broken because every advance of reskilling only appears as a form of real subsumption and hence cannot be a basis either for autonomy in the productive sphere or as a placeholder for the hand’s future emancipation (or its totipotentiality, as John Roberts has put it).[14] No emancipatory effect necessarily follows either from deskilling or reskilling; art has become a bricolage of advanced and archaic techniques, and it is often enough the archaic ones, such as painting, drawing, or ceramics, that are more open to the materiality of reproduction and the subject’s entanglement with structure. Artworks since the 1960s tend to move between various loci within that matrix of reproduction and subjectivation, alighting now on art’s closeness to the commodity, now on certain institutions or technologies, or on the affects peculiar to the ordinariness of crisis.[15] Where the hand is evident its gestures often call into question any continuity between the subject as producer and the object produced. Gesture thereby opens onto trajectories that are, by the standards of a more classical subject-object dialectic, perverse. Consider, for example, a Rosemarie Trockel ceramic of 2006, entitled Shutter 1(a). This object evokes a whole suite of modernist shibboleths – the grid, abstraction, resistant materiality, architectural and bodily metaphors – without for all that cohering into something modernist. It is not so locatable; it is mutant Mondrian. Contemporary art proliferates varieties of non-identity: the non-identity of Warhol with his silkscreens, for instance, or of Mike Kelley with his own working-class background, both of which strategies (there have been many others) were vastly unlike the final, desperate claims to expressive immediacy that Jackson Pollock’s generation had made.[16]

Rosemarie Trockel, Shutter 1(a), 2006

It hardly needs to be said that what I am describing here is another way to narrate the phenomenon previously known as “postmodernism.” That term, however, has in recent years increasingly seemed neither precise nor capacious enough to describe the art of the previous half-century. I have no other name to propose. But I can at least say what we ought to name. Failure to recognise the above accounts for the tedium of much recent discourse on modernism. There is little to be gained from (once again) derailing modernism’s supposed ‘teleological’ drive. Rather, we ought to understand what made its ambitions plausible in the first place, and what ruined them.

The argument, to repeat, is that the end of programmatism also means the end of modernism, and that both ends can be described in terms of the changed temporal horizon of the class relation and in particular the proletariat’s attitude towards the value-form (on a fundamental structural rather than a conscious level). To restate the point in somewhat different words, we can say that modernist art must negate itself because its continued existence is seen as at once prefiguring and preventing conscious direction of the value-form under socialism, whereas art after the eclipse of programmatism no longer relates to a real horizon of the value-form’s socialisation but only to that of its abolition. Art no longer embodies the value-form’s utopian moment because restructuring of the class relation has annihilated the particular kinds of struggle by which its realisation could have been imagined. This definitively came to pass in Western Europe in the 1960s and ’70s, with the deliquescence of the last remnants of the neo-avant-garde into the catch-all known as contemporary art. If we can speak of historical transformations of the value-form, which is also to say of the class struggle, then we can use this analysis as a way to grasp transformations of its intimate other: the ‘art-form,’ if we can call it that.

Keep in mind that if this chiasmus is anything it is at least in part a map of ideological closure, that is to say, of modernism’s myths. The workers’ movement was not in any real way dependent on the artistic avant-garde, nor, of course, were the two formations necessarily aligned. If it was long the case, however, that the negation of art was a real force in the making of art, as I have shown in the example of Mondrian, I am sure that this is because the futurity of revolution along programmatist lines was intuitively known as art’s own occluded content.

A final note on politics and the writing of history. There may little to distinguish my account of art since the 19th century from any number of others. This is really the case, because as far as I am concerned a reading of art in terms suggested by revolutionary theory has no need to bring itself to the marketplace of academic fashions. Revolutionary theory is not a general model of culture or a new tool to add to our boxes alongside poststructuralism or phenomenology or anything else. Its entire interest for historians of art, in their capacity as such, has to lie in the kinds of description it makes possible. Anything beyond this is a matter of commitments that do and should exceed our identities as scholars.

Daniel Spaulding <daniel.spaulding AT yale DOT edu> is a doctoral candidate in the Department of the History of Art at Yale

Note:

I presented an earlier version of this essay at the tenth Historical Materialism conference in London (November, 2013). I would like to express my thanks to Benjamin Noys, who invited me to participate, as well as my fellow panelists, Jaleh Mansoor, Marina Vishmidt, and Anthony Iles. Dan Levenson, Nicole Demby, and Benedict Seymour also generously shared their thoughts on my text. Any remaining faults are of course my own responsibility.

Footnotes

[1] See especially: Peter Bürger, Theory of the Avant-Garde, trans. Michael Shaw, Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1984; Benjamin Buchloh, ‘The Primary Colors for the Second Time: A Paradigm Repetition of the Neo-Avant-Garde’, October 37 (Summer, 1986), pp. 41-52; Hal Foster, ‘What’s Neo About the Neo-Avant-Garde?’ October 70 (Autumn, 1994), pp. 5-32.

[2] Both are makeshift constructs, however. I use the terms only because they have attained a certain currency. See: Endnotes, ‘Communisation and Value-Form Theory,’ Endnotes 2 (2010), endnotes.org.uk/articles/4

[3] I borrow both the photograph and the story of Karl Ioganson from Maria Gough’s The Artist as Producer: Russian Constructivism in Revolution, Berkeley: University of California Press, 2005.

[4] Yve-Alain Bois, ‘The Iconoclast,’ in Bois et al, Piet Mondrian, 1872-1944, Boston: Little, Brown & Co., 1994.

[5] T.J. Clark has recently considered Cubist ‘room space’ at length, in Picasso and Truth: From Cubism to Guernica, Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2013.

[6] This is a somewhat obscure point, because elsewhere the repetitive grid was, of course, one of modernist art’s key devices. Mondrian, however, associated both repetition and symmetry with natural rhythms (the recurrence of the seasons, or the bilateral symmetry of plants and animals), and consequently saw these forms as dangerous to his totalising anti-naturalistic art. He explained it thus in 1919: “Rhythm becomes determinate: naturalistic rhythm is abolished. Rhythm interiorized (through continuous abolition by opposition of position and size) has nothing of the repetition that characterized the particular; it is no longer a sequence but is plastic unity. Individuality typically manifests the law of repetition, which is nature’s rhythm, as law characterized by symmetry. Symmetry or regularity emphasizes the separateness of things and therefore has no place in the plastic expression of the universal as universal.’ (Piet Mondrian, Natural Reality and Abstract Reality: An Essay in Trialogue Form, trans. E.M. Beekman, New York: George Braziller, 1995, p.40.) Two decades later, the artist’s attraction to boogie-woogie music would follow a similar logic – he admired syncopated rather than regular repetition.

[7] The following analysis takes its cue in part from Theodor Adorno’s aesthetics.

[8] These claims are adapted from Rosalind Krauss, The Picasso Papers, New York: Farrar, Strauss, and Giroux, 1998.

[9] See: George Baker, The Artwork Caught by the Tail: Francis Picabia and Dada in Paris, Cambridge: The MIT Press, 2007.

[10] Bürger uses this term in Theory of the Avant-Garde.

[11] As the editors of Endnotes have recently said: ‘[T]he only “contradiction between” is the one with which Marx begins volume one of Capital, namely, the contradiction between use value and exchange value.’ (‘Editorial’, Endnotes 3 [2013].) If I here speak of a ‘contradiction’ between art and value, it should be understood that I am always in fact referring to a specific mode of this more fundamental contradiction.

[12] T.J. Clark, Christopher Gray, Donald Nicholson-Smith, and Charles Radcliffe, unpublished text (1967); available at http://www.cddc.vt.edu/sionline/si/modernart.html.

[13] To forestall a misunderstanding: this is not to say that destruction of the value-form is the content of revolutionary practice or its sine qua non. Rather, destruction of the value-form is implied in whatever practice would destroy the capitalist mode of production. Such a practice would presumably be motivated by much more immediate factors.

[14] Roberts, The Intangibilities of Form: Skill and Deskilling in Art after the Readymade, London: Verso, 2007.

[15] On the latter topic, see: Lauren Berlant, Cruel Optimism, Durham: Duke University Press, 2011.

[16] Which is not to deny that the ‘historical’ avant-garde frequently did things that look very much the same. That many of the characteristic devices of art in the later 20th century were made possible exactly by a recovery of the prewar avant-garde (most notably of Duchamp) is an important wrinkle in my account and a reminder that the history of art is not so linear as this essay perhaps threatens to make it seem. At the same time it is impossible to mistake the utterly transformed social bases of the two formations. On this point, I am particularly indebted to Jaleh Mansoor for articulating how the readymade transformed from a discrete object (or discursive gesture) into a matrix (or condition) in the course of its postwar ‘repetition.’ (Paper delivered at the tenth Historical Materialism conference, London, November 2013.)

Info

Aesthetic Education Expanded is a series of 12 articles commissioned by Mute and published in collaboration with Kuda.org, Kontrapunkt, Multimedia Institute, and Berliner Gazette. It is funded by the European Commission. A central site with all contributions to the project can be found here: http://www.aestheticeducation.net/

The series looks at the contemporary afterlife of the project of ‘aesthetic education’ initiated in the 19th century, from the violent imperatives of training and ‘lifelong learning’ imposed by capitalism in crisis to informal projects of resistance against neoliberal pedagogy and authoritarian repression.

Expanding the scope of the aesthetic in the tradition of Karl Marx to include everything from anti-austerity riots and poetry to alternative and self-instituted knowledge dissemination, the series encompasses artistic, theoretical and empirical investigations into the current state of mankind’s bad education.

Aesthetic Education Expanded attempts to open up an understanding of what is being done within and against capital’s massive assault on thought and action, whether in reading groups or on the streets of a world torn between self-cannibalisation and revolt.