How should the education system be reshaped in order to prepare our students to be able to face an uncertain future, a changing future?

– Sing Kong Lee, Director, National Institute of Education, Singapore, in conversation with Pearson, London[1]

Our vast secondary schools are among the last great Fordist institutions, where people in large numbers go at the same time, to work in the same place, to a centrally devised schedule announced by the sound of a bell. In most of the rest of the economy people work at different times, often remotely and through networked organisations […] The bounded, stand alone school, as a factory of learning, will become a glaring anomaly in this organisational landscape.

– ‘The Shape of Things to Come: personalised learning through collaboration’, by Charles Leadbeater, Department for Education and Skills, UK (2005)

The world’s biggest education corporation, Pearson, invited Sing Kong Lee to London to share the secrets of Singapore’s education success. He describes the evolution in the late ’80s from ‘efficiency driven education’ for the industrial economy, to ‘ability driven education’ for the knowledge economy. Whereas ‘efficiency driven education’ streamed students to learn skills and knowledge as quickly as they could, ability driven education required

….other attributes such as ability to apply your knowledge, ability to think creatively, ability to design innovatively, and how to apply your knowledge to convert it into value.

Pearson employees nod and take notes. And now, Lee informs them, we have moved into a new and ‘uncertain’ period in which ‘it is estimated that knowledge will double every two-and-a-half years’ (sic). Employers need students who can work as a team, collaborate and ask questions. But it is not sufficient to make students ‘work-ready’. They must also be out-of-work-ready: they must have the resilience to face uncertainty, must be self-directed and lifelong learners able to re-skill in line with evolving knowledge, as well as concerned and active citizens who can look after ‘the group that is left behind’. His hosts praise him for his clarity. Although of course they knew it already.

Pearson depicts its vision of the future in three-minute films: swelling music accompanies smiling young people of various ages interacting educationally with floating computers in slightly different ways. In many respects the future doesn’t look that unlike the present. A boy and his computer work on a project to save the world’s water resources before mom interrupts to say dinner’s ready. Dad’s hologram says he can’t make dinner because he’s in the army working on a clean water project (water is a recurring theme of the future). The family looks the same, and the computer looks the same, except that it appears on all surfaces and responds when you wave your hands about. Microsoft’s vision of the future is almost identical to Pearson’s: a teacher sitting on an aeroplane simultaneously monitors a school in India and a school in America (who are learning about water); business women drink computery cups of coffee which, when finished, declare they are ‘Ready to work!’; everything is smiling, empty and white.[2]

If their visions are limited when it comes to technology and the family, it’s in the smiling white emptiness that these corporations have really let their imaginations run wild. This is a future in which teachers have space and time – she sits alone in a huge white room empty of children discussing the statistics and timetables of one child via video link with some other colleague, presumably in some other huge white room somewhere else. And the students are quiet when they should be quiet, and animated when they should be animated. With the help of their computers, they study diligently in their bedrooms and on the bus home. Five-year-olds are transfixed by maths puzzles on their tablets, teenagers from all over the world enthusiastically interface about water.

Although these are essentially promotional videos rather than honest assessments of the future of education, they allude to many themes that are already evident in the restructuring of education systems across the world: computer-led lessons; ‘team’ work; skills and project-driven (rather than subject-based) learning; standardised testing; self-directed learning; casual and de-unionised teaching staff; increased school hours; and increased competition between schools and students. These themes are often discussed and disguised under one heading: ‘personalised learning’.

Personalised Learning

The education department document quoted at the beginning of this article, ominously named The Shape of Things to Come, summarises what ‘personalised learning’ actually means. Although written in 2005, the themes it describes are still very much alive in state and corporate plans to reshape education. The document was written by Charles Leadbeater, who wrote a book in the 1980s predicting the rise of flexible employment[3] and his latest book, We-Think, argues that consumers ‘want to be participants in the creation of services they want’.[4] He was also Tony Blair’s advisor and co-responsible for writing Bridget Jones’s Diary. Hardly surprising, then, that Blair’s Department for Education and Skills saw him as the perfect candidate to set out their vision for the future of schooling.~

Like Sing Kong Lee, Charles is refreshingly clear. He argues that under the old ‘Fordist’ model of education, children are an ‘untapped resource’. He then explains what it would mean to tap them: getting children to become ‘more engaged and motivated investors’ in their own education, by ensuring that they are investing ‘hope, effort, time and imagination’ into ‘producing’ their learning. This education will be learner-led while remaining within the framework of national standards.

That is the ultimate goal of personalised learning: to encourage children to see themselves as co-investors with the state in their own education.

The document describes how each student will have their own personal timetable, divided between work in small groups, some class lessons and one-on-one tuition. By secondary school, this builds up to seven hours a week spent ‘learning how to learn’, in which students work in self-managed groups to complete a task together to a deadline. Learning how to learn looks a lot like learning how to work.

Apart from children, other ‘under-utilised resources’ in the Fordist school include families, communities and parents. In fact Leadbeater argues that ‘[a]ll the resources available for learning – teachers, parents, assistants, peers, technology, time and buildings – have to be deployed more flexibly.’ Some flexible proposals include: the technology that students use at home and which they ‘regard as their property and so take responsibility for’ will be utilised in the school environment[5]; older children will be mobilised outside of the school building, spending time with employers and social enterprises; school leavers and parents will be brought into school to help deliver teaching; and the remaining professional teachers will design the teaching programmes, provide personalised learning plans and timetables for each child, phone students’ parents at least once every two weeks, advise students one-on-one, and teach in other schools. Even school opening hours will not be fixed:

Schools will not personalise learning within the confines of the standard, 8-til-5 working day.[6]

Responding to the requirements of their students, schools must have ‘more flexible scheduling modelled on airports’ as well as on businesses like BT and Borders bookstore. Apparently BT extended its working hours to suit the needs of its workers, who ‘want to work different hours and to provide a differentiated service to customers’. And Borders bookstore is an example of a successful organisation that is open early and closes late.

Since the document was written, Borders bookstore has closed for good. The risks for stability – the likelihood of school ‘failures’ and closures – associated with resource flexibility and innovation are not mentioned. But there is no reason why this uncertainty couldn’t be justified as part and parcel of personalised learning. After all, if you want to prepare students for an uncertain future, what better way than to give them an uncertain present?

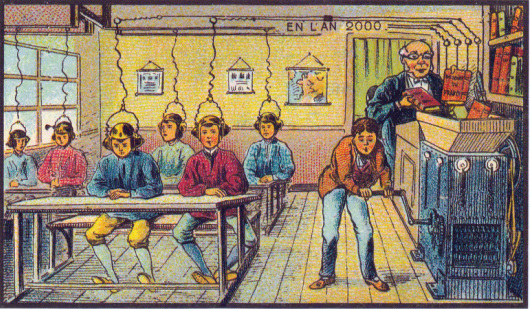

‘At School in the Year 2000’. A postcard from the World’s Fair in Paris, circa 1899

The uncertain present: USA

I always think, ‘never send a person to do a machine’s job.’

– Frank Baxter, Investment bank CEO, Former Ambassador to Uruguay under George W. Bush and ‘blended learning’ funder.[7]

The job Baxter was talking about: teaching maths and literacy to children. But to which children?

Pat Bassett, former President of the USA’s National Association of Independent Schools, talks excitedly about the future of education in elite schools.[8] As in Pearson’s video visions of the future, these students have all the space, time and resources that they need. And, as in Lee’s post-fordist pedagogy, they learn how to collaborate, innovate, ask questions and apply their knowledge to create value. These students are not taught by machines, but by ‘inspirational teachers’ who ‘throw away the textbook’. Bassett describes how, through designing mosquito nets for children in rural Tanzania or creating robots that launch grenades, these students secure US patents, learn high level physics and win places at MIT. These are the leaders of the future. They are making the machines, rather than being made by them.

If you want to find places where teaching is a machine’s job, you must look to the US Charter School system, experimental schools for America’s ‘low-income and urban students’, and an inspiration for the UK government’s Free Schools.[9] There are two particularly high profile attempts to roll out machine-led personalised learning within the Charter School framework – Carpe Diem schools and Rocketship schools. Both are trying to create a school that is ‘cost effective’ whilst also giving students a sufficient level of ‘proficiency’, with the aim of mass-producing their models across the US. Both operate with a ‘blended learning’ system, in which children move between computer-led instruction, teacher-led instruction and work in small groups.

When Charter School Carpe Diem lost the lease on its original building it was forced to find a new location. One of the few available buildings was an empty call centre, a vast room criss-crossed with computers inside cubicles. But this didn’t deter Rick Ogston, founder of Carpe Diem. In these cubicles he saw the future of education. A student clocking in here would develop incredibly aspirational aspirations.

The call centre is now filled with students. They spend most of their day on computers, working from lecture courses on the internet. The computers continuously collect data on their performance which is relayed back to the teachers. At different times in the day they get a chance to break out into group work or lectures and talk to their teachers about particular issues they have problems with. Not too frequently, however. The school has 300 students. It has four teachers. That’s a student teacher ratio of 75 to 1.[10] Unsurprisingly, the saving in staffing costs means that it spends $2,600 less per year per pupil than the average school in the state.[11] Carpe Diem has secured funding for new schools by promising to pay back loans with these savings. As Carpe Diem funder Dan Peters eagerly points out, the schools’ efficiency provides an opportunity to break free of the goodwill of philanthropists and let profit drive expansion.[12]

Rocketship CEO John Danner had the perfect CV for founding a Charter School: he started up a Silicon Valley advertising internet software company and has three years of teaching experience. Rocketship schools have received money from various philanthropic foundations, including a $100,000 grant to spend on public relations.[13] The philanthropists put money in, the parents put time in: they are encouraged to come into the school as volunteer teaching assistants, with some working unpaid for over 15 hours a week.

After the daily morning ‘launch’ in the playground, in which parents, students and teachers chant together about success, students spend two hours a day in the Learning Lab, which distinguishes itself from the call centre at Carpe Diem by being painted in primary colours to match the primary age children. A document sympathetic to the Rocketship model describes the Learning Labs:

When the children shuffle in, they sit down and follow signs reminding them of the proper learning posture: headphones on, no talking, raise your hand if you need help.[14]

Inside the cubicles, every child has a personalised ‘playlist’ of learning. To begin with, students in the Learning Lab were not supervised by teachers, but only by ‘Individualised Learning Specialists’ – hourly waged teaching assistants. Unfortunately that wasn’t enough for some children, and so, in the spirit of constant innovation, some teachers have now been brought in to supervise the Learning Lab sessions. Even so, the small ratio of students to teachers means that money is still saved and ‘productivity’ per teacher boosted:

The two hours per day of computer instruction will still allow teachers to avoid burning time teaching or reviewing basic concepts that machines do better.[15]

The Learning Labs together with the fact that the school does not provide art or music means that Rocketship has six fewer teachers and six fewer classrooms per school and so saves substantially on building and staffing costs. It also cuts the cost of teachers by hiring recently qualified and so lower paid teachers – about half have less than two years’ teaching experience.[16] As a result, it is able to spend 15 percent less for each child than allocated by the state,[17] and says its staffing mix results in benefits of about $336,000 per school per year.[18]

With a small part of its huge savings it is able to pay its teachers at least 15 percent more than the same teachers would get paid at other schools.[19] If the higher salary isn’t enough to keep teachers out of trouble, then the daily monitoring of their lessons should do the job. And the teachers Rocketship recruits are less likely to strike anyway: three quarters of Rocketship teachers come from Teach for America.[20] Teach for America (which spawned Teach First in the UK) gives graduates from elite universities six weeks training to commit to two years teaching in ‘under-resourced schools’. Given that many are intending to go into business or educational management after these two years, permanency is not such an issue. In an interview with PBS News Hour one teacher says she has ‘an at will employment contract, or non-contract I guess’, but insists that her good work means she won’t get fired. Another teacher tells the channel:

I’m making more money than I made when I was part of a union. I have more job security, I would say, than when I was part of a union, so I’m not sure what I would need a union for.[21]

CEO Danner agrees – no way can unions come into Rocketship – it is a start-up, they would only get in the way of daily change and innovation.

But even Charter School devotees admit that this daily change and innovation has its downsides. Various technology related complaints include: teachers don’t know what the children have been doing on the computers, because the data isn’t clear enough; students who get through the lectures quickly reach a dead end, and have to wait for the software makers to catch up; bandwidth is not sufficient to allow all the students to watch online lectures at once; computers break down. These are all things that can be refined through investment in the technology, something that the Gates Foundation is already committing funding towards. Other problems are slightly harder to solve, and are nicely summarised in this analysis of another blended learning experiment:

The algorithm didn’t completely account for the human factor in education.[22]

If personalised learning can’t account for the human factor, then education providers have a problem. Some children won’t sit quietly in front of a computer for hours, others just click things randomly until they disappear. Diane Tavenner, founder of Summit Schools, another blended learning school chain, admits that this is ‘messy stuff’, but, like any product, ‘you have to test and iterate’.[23]

In a start-up, some products are bound to fail. And a few Learning Lab rats get lost along the way.

Selling toys

Thanks to Bill Gates and Pearson, failure can be measured and more money can be made. Together they have created the Common Core curriculum – a way to standardise and compare test results across the US, something that becomes even more necessary for employers when education is a free market of different providers. These standards also make it easier to employ teachers who are not professionally trained: the curriculum gives scripted lessons, allowing just about anyone to deliver the content. And the content is helpful too. Not only do children learn that Bill Gates is a great man, but they begin to learn about their role in the system, as well as becoming the targets of its advertising.

In the first unit of the first grade, teachers must ‘have students learn’ the following vocabulary:

goods

services

want

need

collects

taxes

producers

farmers

consumers

earn

income

sells

saves

choices

cash register

inventory

groceries

average [24]

As part of ‘small group instruction’ teachers must then teach the six year olds the following:

Explain that Joe, the boy behind the table, is selling his old toys. He is the producer—he is providing goods for other people to buy. The other boy is buying some of Joe’s toys. He is giving Joe money and taking some of Joe’s goods, the toys. He is the consumer.

Help children think of another scenario they could draw that shows one person selling goods and another person buying the goods. […]

When children have drawn their picture, help them label the producer, the consumer, and the goods.[25]

Not only are children encouraged to think of their toys as goods, but they are encouraged to consume more goods through product placement. Although the Common Core exams are not made public, an eighth grader who took the test describes his exam:

The ‘busboy’ passage in the eighth grade test I took was fictional, written about a dishwasher at a pizza restaurant. In it, the busboy neglects to notice a large puddle of root beer under a table that he clears. His irate employer notifies him about the mess, and he cleans it up […] the root beer was referred to at one point as Mug™ Root Beer. It was followed by a footnote, which informed test-takers that Mug™ was a registered trademark of PepsiCo.[26]

The same boy says that they were given less time and harder questions than on previous exams. Many students were not able to finish the exam in the time allocated. Teachers have complained about the high level of stress the children are put under, and assessors have asked for official guidance on what to do when students have vomited on their papers.[27]

Another money-making opportunity that schools offer is data collection. Technology company Knewton provides personalised learning software to the world’s biggest education corporations. But Knewton founder and CEO Jose Ferreira has no qualms about sharing the real advantages of personalised learning:

We really have more data about our students than any company has about anybody else about anything, and it’s not even close.

He can hardly contain his excitement when he says that Knewton has five orders of magnitude more data per user than Google.

So the human race is about to enter a totally data-mined existence, and it’s going to be really fun to watch […] When Tom Cruise walks through the mall in Minority Report and the ad beams right into his eyes and says, ‘Hey Mr Cruise you should go on that Caribbean vacation you’ve been thinking about’, I know some entrepreneurs who’ve been working on that technology right now.[28]

The more personalised learning that goes on, the more refined the data will become, until, Ferreira promises us, they will be able to tell what each learner had for breakfast. That’s the kind of information that would be very useful to the makers of Mug™ Root Beer.*

*Registered trademark of PepsiCo.

The uncertain present: UK

‘We will not allow the reductions in funding to adversely affect our capacity to improve; indeed the closure of poorly performing courses will improve our success rates’, Hackney Community College, May 2014.

Michael Gove has given every primary school a King James Bible and thinks children should speak Latin. You might be forgiven for thinking the Education Secretary is not surfing the personalised learning wave. And if you have watched Jeremy Paxman’s hilarious interview with Lottie Dexter, the head of the government’s project to roll out computer coding lessons across the UK school system, then you might conclude that the government are more interested in giving a Tory activist a job than innovation in education.[29] But you would be wrong.

Thanks to Gove, education is becoming much more flexible. Not only are local authority run schools being incrementally freed from nationally agreed pay and conditions, but the Conservative Party’s Free Schools are taking Labour’s Academies to the next level: they can be run by anyone, anywhere, anytime, anyhow. And the most successful are looking to US Charter Schools for inspiration.

Although the examples are endless, this article will focus on a school that is futuristic in a very old school kind of way: the University Technical College (UTC). David Cameron says he wants a UTC in every major town. UTCs are the brainchild of Kenneth Baker, education secretary under Thatcher, who clearly feels he didn’t do quite enough for education when he introduced the National Curriculum, league tables, SATs and grant maintained schools.[30] Supported by university and industry sponsors, they provide 14-19 year olds with a mixture of practical project based courses and academic subjects. Students are readied for work: employers help to shape the curriculum; the timetable reflects the working week, with longer days and shorter holidays; the employer and university sponsors form the majority of the governing body; the classrooms are designed to mirror a workplace environment; and students are expected to work with businesses on ‘real-life’ projects.

The reason given for beginning technical education at 14 is that many students become bored and underachieve if left in mainstream education. So the UTCs take the ‘underachievers’ and the mainstream schools are left with the ‘academic’ students. This sounds suspiciously like a grammar school system. Of course Baker would argue that this is best for everyone: the achieving students will get more space and time for their achievements, and the underachieving students will be freed from their boredom and shaped for the real world by the curriculums of JCB, Merrill Lynch, the Royal Air Force, Rolls Royce, Cisco, the Nuclear Decommissioning Authority, Tottenham Hotspurs FC, Ford, The National Theatre, The National Grid, Middlesex University, the Diocese of Chelmsford, Thames Water…

The campus of Hackney Community College, which hosts London’s first UTC, is a microcosm of educational change taking place across the country. The new UTC is sponsored by BT, Homerton University Trust, the University of East London and, for reasons that can only be suicidal, Hackney Community College. The UTC occupies the community college’s old courtyard, and directly competes with the college, offering some of the same courses that it provides/provided. While the college was facing numerous cuts and redundancies, with subjects such as plumbing, ICT, art and media seriously reduced or even closed down, millions of pounds were ploughed into the new UTC, focussed on two of London’s ‘growth industries’: digital and creative media and health. If this weren’t enough, View Training – which provides employability courses for adults – now also operates on campus in classrooms previously used by the community college. At the time of writing the community college faces many more redundancies and a further £1.75 million in cuts.

Hackney UTC provides more evidence of an attempt to move ‘underachieving’ students out of mainstream school and into work based education. According to UK inspection body Ofsted, the new school has a significant minority of students with previously disruptive educational experiences and a higher than average number of students with special educational needs. (And if the work-based education doesn’t guarantee these students work after they leave, the Job Centre can always offer them more work-based education conveniently provided by View Training on the same campus.)

But the system’s not quite as smooth as might be hoped. Initially only providing education up to age 16, the UTC had to delay its expansion to the sixth form for one year due to the low number of applicants. And an Ofsted inspection of Hackney UTC from February 2014 only seems to be happy with the sponsors, who apparently bring an impressive range of skills from the business, health and education sectors. As governors, they apply their expertise thus:

They carefully scrutinise all evidence about the college’s performance that they are provided with, but further seek to test out the accuracy and reliability of information. This is achieved through the use of external consultants and a rigorous approach to analysing data, which includes a focus on national benchmarks. [31]

Despite their rigorous data analysis, the Ofsted report found that in all other respects the college is ‘not good’ and ‘requires improvement’. The report was published in early February 2014. In March 2014 the Principal announced her resignation. Educational innovation doesn’t seem to be going so well. And this is an experience shared across the country.[32]

But a few steps ahead of us, Rocketship CEO Danner is confident that they have almost perfected a cost-efficient school model.

Now when we’re opening a new school, 50 percent of the result is almost guaranteed unless someone sets fire to the computers. [33]

Setting fire to the computers

Although there was no golden age when children actually enjoyed school, at least in the past there wasn’t an expectation that they’d continue learning their whole life long to keep up with the times. And back in the day, the frustration they felt at school could be channelled by teachers into art, PE and anti-establishment rock music. It was a teacher that organised the choir of school kids for Pink Floyd’s number one hit:

We don’t need no education

We don’t need no thought control

No dark sarcasm in the classroom

Teachers leave them kids alone

Hey teacher leave them kids alone

All in all it’s just another brick in the wall

All in all you’re just another brick in the wall

By reducing the role of the teacher, education providers won’t only save money, but will also make teacher strikes less likely and less effective. But without teachers’ critical voices and dark sarcasm, they will also destroy education’s more subtle systems of control: the teachers’ grip on the pesky ‘human factor’ in education.

Whereas teacher-led practical learning in elite schools may be effective in producing entrepreneurial and confident leaders, in understaffed schools without art, music or PE, the immediate aim of selling toys trumps the long term aim of producing eager labourers and consensual citizens. Children developed in Learning Labs can be tapped for data or encouraged to consume, but they are very far from being, or considering themselves to be, producers of their own education. The more power is taken away from teachers in the name of personalised learning, the more children will recognise their education as alien and impersonal. And whatever Leadbeater says, the old Fordist model remains: as long as workers need a free babysitting service, their children will continue to go to the same places every day in their hundreds, knowing that they have nothing to look forward to but casual jobs and long periods of unemployment. In a system where everyone and everything has been made flexible, children are the one thing that gets in the way.

Aside from vomiting on their papers and staring up at the ceiling, children have also demonstrated a more active way of resisting personalised learning. The charity One Laptop per Child (OLPC) left a box of computers in an Ethiopian village to see whether the children could learn the English alphabet without a teacher. Some of them succeeded, but they also managed to hack the computers to activate features that the charity had disabled. OLPC hailed this as an unexpected but welcome result of the ‘experiment’, arguing that the importance of tablet learning is not so much the content, as getting children to ‘learn how to learn’. Hacking demonstrates the kind of inquiry and creativity that today’s economy needs. However, when a $1 billion educational project to give an ipad loaded with Pearson software to every child in Los Angeles ended in students altering the security settings to surf non-educational sites, the district panicked. The School District Police Chief said he feared that this could lead to a ‘runaway train scenario’, and recommended that the district delay distribution and prevent students from taking tablets home. It is not clear where he saw that train running, but it was definitely somewhere scary.[34]

Perhaps the possibility of school students resisting en masse feels a long way off. But even now there are more arson attacks on UK schools than days in the year.[35] And we shouldn’t forget that the street based events of 2010 and 2011 were led by teenagers. There’s a reason why it is only elite students that are being taught to make grenade launchers. If children have an uncertain future, then so too does capital.

Michelle Jones spent too much of her life at school

Footnotes

[1] See ‘Reimagining Learning: In Conversation with… Sing Kong Lee’, Pearson, 4

December 2013, http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ewQKbAUa9PQ

[2] Microsoft Vision of the Classroom of the Future, http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=aJu6GvA7jN8

[3] Charles Leadbeater, In Search of Work, London: Penguin Books, 1987.

[4] Charles Leadbeater, We-Think: Mass innovation,not mass production, London: Profile Books Ltd., 2008, p.98.

[5] Although he doesn’t say it, this could encourage students, even after they have left school, to see their computers as the means through which they can ‘reskill’, boosting the market in learning apps. This would also encourage parents to buy their children the latest technology in order to keep up with the school’s demands.

[6] Leadbeater would be shocked to hear that the current school day usually starts after 8am and finishes well before 5pm.

[7] See Laura Vanderkam, Blended Learning: A Wise Giver’s Guide to Supporting Tech-assisted Teaching, Washington DC: The Philanthropy Roundtable, 1 April 2013, p.43, http://www.philanthropyroundtable.org/file_uploads…

[8] Pat Bassett, TEDx talk, 12 April 2012, http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=y0cqrhvgBB0

[9] Vanderkam, Blended Learning, op. cit., p.35.

[10] Ibid., p.50.

[11] Ibid., p.51.

[12] Ibid., p.52.

[13] Ibid., p.41.

[14] Ibid., p.36.

[15] Ibid., p.37.

[16] ‘Can Rocketship Launch a Fleet of Successful Schools?’, PBS News Hour, 28 Dec 2012, http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hOsRkCFfsjo

[17] Vanderkam, Blended Learning, op. cit., p.37.

[18] Brad Bernatek, Jeffrey Cohen, John Hanlon, Matthew Wilka, ‘Blended Learning in Practice: Case Studies from Leading Schools’, Austin: Michael and Susan Dell Foundation, 2012, p.27.

[19] PBS News Hour, op. cit., http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hOsRkCFfsjo

[20] Ibid.

[21] Ibid.

[22] Vanderkam, Blended Learning, op. cit., p.59.

[23] Ibid., p.50.

[24] Susan O’Hanian, ‘Common Core: Asking First Graders To Extract and Employ Evidence About Producers and Consumers’, susanohanian.org/core.php?id=675

[25] Ibid.

[26] Isaiah Schrader, Valerie Strauss, ‘Eighth grader: what bothered me most about the new Common Core test’, Washington Post, 8 May 2013.

[27] ‘Editorial: The Trouble with the Common Core’, Rethinking Schools, Vol.27, No.4 Summer 2013, http://www.rethinkingschools.org/archive/27_04/edi…

[28] ‘Of Big Data, Corporations and Fleas’, Teacher Solidarity, http://www.teachersolidarity.com/blog/of-big-data-…

[29] If you haven’t seen it, and need a laugh, you should: ‘Teach children to write computer code’, Newsnight, BBC2, 5 February 2014, http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-7x7GYItzS4

[30] Schools freed from local authority control.

[31] ‘School report: Hackney University Technical College’, Ofsted, Crown Copyright, 2014.

[32] A document leaked to the Observer shows the government is worried about how messy innovation can be: ‘[Problems with Free Schools] include operating in temporary sites without a clear permanent home; new, inexperienced and often isolated trusts needing to upskill themselves to run a school for the first time; instability in principal appointments and senior leadership teams,’ from ‘Future Academy System: Lord Nash session’ quoted in Daniel Boffey and Warwick Mansell, ‘Michael Gove’s bid to limit fallout from failing free schools – revealed’, The Observer, 5 April 2014.

[33] Vanderkam, Blended Learning, op. cit., p.41.

[34] Howard Blume, ‘LAUSD halts home use of iPads for students after devices hacked’, Los Angeles Times, 25 September, 2013, http://articles.latimes.com/2013/sep/25/local/la-m…

[35] Anthea Lipsett, ‘Nearly 3,000 school arson attacks in two years’, The Guardian, 22 May 2009.

Info

Aesthetic Education Expanded is a series of 12 articles commissioned by Mute and published in collaboration with Kuda.org, Kontrapunkt, Multimedia Institute, and Berliner Gazette. It is funded by the European Commission. A central site with all contributions to the project can be found here: http://www.aestheticeducation.net/

The series looks at the contemporary afterlife of the project of ‘aesthetic education’ initiated in the 19th century, from the violent imperatives of training and ‘lifelong learning’ imposed by capitalism in crisis to informal projects of resistance against neoliberal pedagogy and authoritarian repression.

Expanding the scope of the aesthetic in the tradition of Karl Marx to include everything from anti-austerity riots and poetry to alternative and self-instituted knowledge dissemination, the series encompasses artistic, theoretical and empirical investigations into the current state of mankind’s bad education.

Aesthetic Education Expanded attempts to open up an understanding of what is being done within and against capital’s massive assault on thought and action, whether in reading groups or on the streets of a world torn between self-cannibalisation and revolt.